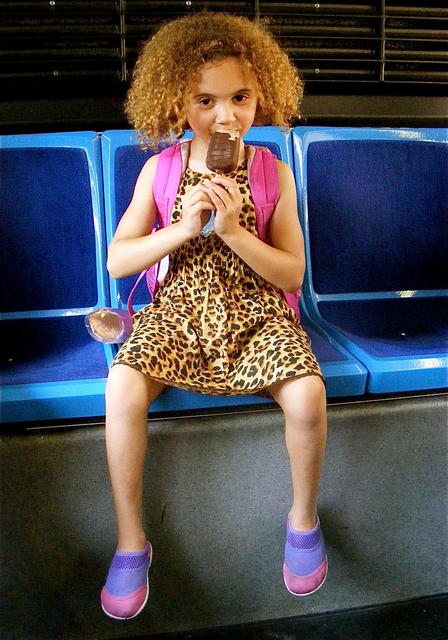

I swung off the curb and onto the M4 bus relieved to finally step out of the thick, simmering street air of a New York City late summer afternoon. I noticed the self-possessed girl pictured here even before the bus began its stuttering trip through borderlands of Morningside Heights where the Columbia’s irreverently shabby coffee houses and luxury hair salons eventually concede to Harlem’s brimming discount stores and fruit vendors.

She struck up easy conversation with me, asking first about my camera. Fifteen blocks, three stops and one extended honk passed as I learned that she was commuting home from school with her father, loved double chocolate ice cream, and was going roller skating at Riverbank State Park later that evening. Her father laughingly nodded his permission when I asked if I could take a photo of his daughter. Two stops later, they were gone. The memory of this girl and her indisputable conversational and physical confidence has, however, lingered with me for some time.

I marveled at her impervious sense of self as she stared squarely at my lens, poised in a faux bite of her snack, legs akimbo with her presence somehow filling an entire row of NYC bus seats. This snapshot captures a unique moment in this girl’s personal history before she has seriously taken up the endeavor of becoming a gendered body. Judith Butler writes that each of us “are born male or female, but not masculine or feminine … ‘femininity [on the contrary] is an artifice, an achievement, a mode of enacting and reenacting received gender norms which surface as so many styles of flesh.’” There was nothing in this young girl’s demeanor during the brief time I spent with her that hinted at the presence of this gendered production. The past fifty years have clearly witnessed a great widening of the professional horizons for women in the United States; however, the persistence of a wide variety of bodily-based gendering projects makes me puzzle at the conclusiveness of women’s progress. In 1998, Sandra Barky introduced Michel Foucault’s famous theory, which contends that micro-processes guarantee docile bodies, to the gendering process. Bartky argued that a specific repertoire of gestures, postures, and movements are daily socialized into the type femininity that women engaging in patriarchal body projects hold as a goal. Remembering my own experience when I was the age of this photograph’s subject, I can see how “the hidden school curriculum of disciplining [my] body” had specific gender goals and, in the end, produced me as a woman who is more physically docile than my male counterparts. The bodily and vocal deportment of this girl serve as a counterpoint to my own embodied experience. This difference is meaningful on several accounts: This young girl displayed an elevated, joyous conversational volume that is discouraged, especially in girls, in educational settings. She professed her “love” for a high-calorie indulgence as well as a hearty enjoyment of physical activity that some women more invested in disciplining their bodies might not proclaim. Third, the subject is shown here holding her body in a version of what Marianne Wex, who documented the differences between masculine and feminine body postures through a series of street photos, calls the “proffering position,” serving to maximize the space a, typically male, body takes up.

Though our interaction was short and I can claim to know almost none of the developmental and familial circumstances of her life, her seeming immunity to the micro-processes of patriarchal power described above has served as a reminder of their strength in my life ever since. If such an unusual absence is so starkly etched into my memory, then this image serves as a call for each of us to remain vigilant towards their usual presence and our participation in their mandates. For, as Bartky goads “women cannot begin the re-vision of our own bodies until we learn to read the cultural messages we inscribe upon them daily.”

(1)Butler, Judith. 1985. Embodied identity in de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Paper presented at the American Philosophical Association, Pacific Division.

(2)Bartky, Sandra Lee. 1998. “Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patrirchal Power” in The Politics of Women’s Bodies. New York: Oxford University Press.

(3)Martin, Karin. 1998. “Becoming a Gendered Body: Practices of Preschools” in American Sociological Review 63: 494-511.

(4)Anyon, Jean. 1980. Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. Journal of Education 162: 67-92.

(5)Bordo, Susan. 1993. Unbearable Weight. Berkley: University of California Press.

(6)Wex, Marianne. 1979. Let’s Take Back Our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. Berlin: Frauenliteraturverlag Hermine Fees.

(7)Bartky, Sandra Lee. 1998. “Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patrirchal Power” in The Politics of Women’s Bodies. New York: Oxford University Press.

[expand title="Commentary on Rachel's Work"]

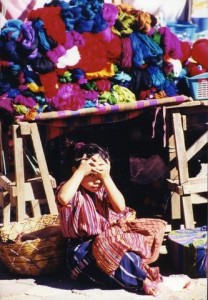

The young Guatemalan girl captured by Rachel Tanur’s lens sits in almost direct opposition to my photograph of a young American girl. Tanur frames this young girl with the tidy chaos of gloriously colorful yarn, perhaps, to draw attention to the strained and somewhat defensive posture of her subject. What this young girl does have in common with the young girl that I featured in my photograph is a relationship to set of overarching patriarchal power structures. This girl’s bodily posture, with tightly crossed legs, interlaced fingers used to shield half of her face, speaks back to the viewer, asking him politely but insistently to go away.

At the very least, this image tells us that someone has educated this Guatemalan girl about her approaching womanhood through her appearance in proper and “womanly” conservative attire. In addition, her reclined, passively resistant posture shows some willingness to control her body to conform to cultural gendered norms. In this way, she shows some similarity to the woman depicted by Marianne Wex’s typical female subjects. Photographed “with arms close to the body, hands folded together in their laps, toes pointing straight ahead or turned inward, and legs pressed together … the women in these photographs make themselves seem small and narrow, harmless; they seem tense; they take up little space.” The young girl pictured here is almost a textbook example of one of Wex’s subjects. Her defiant gesture should not, however, go unnoticed. As she purposefully covers her face to block the camera’s line of sight while simultaneously peering out under her hand mask, this girl expresses a conflicted bodily discipline. Though she polices her body to conform to lady-like carriage and dress, she is seated, unconcerned for her clothing, with one eye winking at the camera.

In closing, it should be considered that her resistant gesture could be partially related to an amplified sense of power she has experienced as the proprietor of the yarn in the marketplace. Mary Crain has argued that the increased earning power that the informal economy often times affords women in developing countries facilitates women’s redefinition of traditional gender roles. Participating in a public, fiscal, and historically male sphere, these “market women” speak and gesture in a far more “assertive and powerful manner” both in and outside the market.

(1)Wex, Marianne. 1979. Let’s Take Back Our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. Berlin: Frauenliteraturverlag Hermine Fees.

(2)Crain, Mary M. 1996. “Ecuadorian Andes: Native Women’s Self-Fashioning in the Urban Marketplace” in Machos, Mistresses, and Madonnas: Contesting the Power of Latin American Gender Imagery. London: New Left Books.

[/expand]